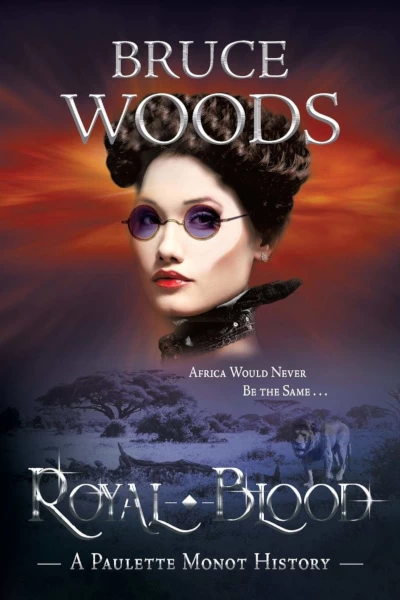

Risingshadow has the honour of publishing a new guest short story by Bruce Woods, the author of Royal Blood.

This story can also be found on the author's Facebook page.

(You can find the previous story here.)

Hearts of Darkness Trilogy #1

by Bruce Woods

Historical and fictional characters come together and change the future of Africa forever. Renowned actress Lady Ellen Terry, detective Sherlock Holmes, financier Cecil Rhodes, hunter/naturalist Frederick Courtney Selous, King Lobengula, and a mysterious, undead adventuress named Paulette Monot become chess pieces in the Great Game, which takes the form of Africa's First Matabele War.

"It is unlikely that anyone will ever read this. In fact, if you are perusing these pages, and you’re not one of the Kin (“vampires” to the uninitiated), it is almost certain that there’s either been some sort of terrible mistake or that I (Miss Paulette Monot) have decided to take a mortal lover. The latter is perhaps more likely. Lucky you."

Paulette and the Elephant by Bruce Woods

The ring of sandy mud surrounding the water hole was organ-meat gray, sparkled with bits of mica like sign in a gold-digger’s pan. Directly in front of me I could see where an antelope, presumably in mid drink, had sprung to one side and fled. The deep postholes left by its forelegs told me it was kudu or sable sized, though the distortion of the tracks prevented me from making any finer distinctions. Almost atop the hoof prints was evidence of the reason for that flight; the always surprisingly large pug marks of a lion showed where the animal had landed, ending its leap almost precisely where the antelope had been.

Back in the day, one didn’t have to stray far from the haunts of men to still see “Africa red in tooth and claw.” With a delay before I was to begin winding my way back to London to report to Ellen Terry on my Metabele mission, I was indulging in a little time alone, the better to digest what I’d learned during my African adventure and to evaluate my changed status.

Transcribing these notes from my Tessier-Ashpool Recording Device, it occurs to me that perhaps I should attempt to put them in some context. Your narrator (never humble) is one Paulette Monot, a member of the Kin (you’ve probably heard the term “vampire”), and new enough to that state to have accepted a commission from Ms. Terry, “eternal beauty” of the London stage and de facto leader of undead in that metropolis, in order to improve my expectations. Travel being if anything more fraught with delays in that day and age than it is today, I found myself with time on my hands before my return and set off into the surrounding bush alone, guarded only by my .360 Gibbs Farquharson single-shot and mounted on my trusty Horace-Wilkershire Coilcycle, to taste the Dark Continent’s hot air without the spice of crisis.

Game trails, white where the desiccated grasses had been worn away by generations of hooves, radiated everywhere though the bush. And since my Coilcycle, lugged tires or no, preferred these to the surrounding shrubbery, I followed a track to the waterhole mentioned above, and dismounted there to read what the wet soil had to say.

The pool could not have been more picturesque had it been designed to delight. Less than an acre in area, the yellow grass surrounding it gave way to wet earth at the water’s edge, and was further flanked by head-high hay ricks of thorn brush and an esthetic scattering of the acacia trees indigenous to the area. The pool itself was, in one corner, festooned with lily pads, the yellow, fist-tight roses of their blossoms beautifying the scene, and there was evidence aplenty that the life-giving water was well known to the beasts that frequented the area.

My initial exploration complete, I let myself go still in order to better read the messages brought to me by my senses, rather like a chef will attempt to waft the aroma from a cooking pot with her hands. I could hear the faint ticking of my Coilcycle as it cooled; quieter, but no less distinctive, than the sounds produced by a steam or internal-combustion engine after hard running. Insect noises added a sloppy rhythm, and even the sounds of the breeze combing the grasses were clear to me.

My senses of course far transcend the human, and I confess that I have yet to learn all of their uses and limitations, but a distant rumble seemed to strike my very bones like a tuning fork. I waited long enough to note its location and direction of travel, and then moved to one side of the waterhole, not so much retreating as positioning myself.

The sounds, more felt than heard, moved closer. Though limited by the heated air, they must have travelled miles in every direction, and told me that their makers were near at hand and fast approaching. I threw my eyes into the yellow light, blinking and crossing them as if trying to decipher a visual illusion. Once seen a thing can never be unseen, and suddenly they were there, shuffling among the stunted trees, miraculously large.

These were creatures that followed the evolutionary dictum, “If you want to be safe, you must be terrible.” And who were less comfortable with its corollary, “if you are terrible, you must be kind.” Only when very young did they have any natural enemies, and then only when a cow wasn’t close at hand. The sole exception, of course, was mankind, with its guns and spears, its pit-traps and assegais.

And then there was me.

An old matriarch led them, followed by younger cows and their pig-sized offspring. An ancient bull, half-again as large as the others, heavy in the tusk and moving as if the effort were beneath him, ranged to one side of the small herd, to my side to be precise, to serve as the group’s enforcer.

I, of course, stood my ground. My unholy self-confidence should come as no surprise to anyone who knows me. The bull positioned himself some fifty yards from where I stood, his small eyes fixed me like a bug to cork, his great ears wide and trembling as if with the effort to hold them so, and his trunk out and up, snakelike, searching the air for a scent that would tell him what he faced.

I am not a particularly odoriferous thing, and for the most part abstained from any scent calculated to appeal, but I also had no doubt that the seeking nose would uncover some sort of signal. Watching, with my little Gibbs clutched more tightly, it was almost as if I could see the slow calculator of his familial memory placing me within his species’ world of experiences.

I had, you see, shot an elephant in the past, under what at the time seemed desperate circumstances and do so still, and I recognized the moment when his mind solved the puzzle and saw me as an enemy. Without a sound the huge ears folded back against his body, the serpentine trunk curled tight to his chest, and he came at me in rapid strides. His terrible self-confidence was at least the equal of mine.

I am extremely hard to destroy, but I’ve often enough seen creatures struggling to reconstitute themselves in the face of an ongoing attack. One can only regenerate while the energy to do so lasts, and pain is among the last things to cease. It is not an ending that I would cherish, and I was determined not to let it happen to me. Still, I had my rifle and five cartridges, and my uncanny speed and agility. If I could stay out of the grasp of the muscled trunk, I probably had little to fear.

I raised the Gibbs, bemoaning the soft-pointed bullet I’d earlier loaded (which would mushroom on impact; good medicine against cast and antelopes, but not exactly suited to the enemy I faced), and trying to remember the position of the bread-loaf brain, tucked behind inches of honeycomb bone, that I’d been lucky enough to reach once before. I had aimed but not yet fired when, front feet ahead of him and sliding, the bull came to a stop. Again his ears spread, his trunk queried the air.

I’d like to believe he did not smell fear. At any rate, I slowly lowered the rifle. There was no miraculous communication between our species, so I simply stared at his immense bulk, fearlessly in my place, and tried by thought and stance to let him know that the past had been necessary, that I had only been as terrible as the time demanded, and that I offered him and his no harm.

I doubt that even this was communicated. He was, after all, as close to an alien life form as I’ve ever encountered; even the most otherworldly of the creatures I’ve met was not as different as the elephant. This was a species that destroyed its environment while feeding on it, confident that its world was wide enough to assure that the plant life (even trees!) would recover before the herd’s wanderings returned to the area. Though undoubtedly intelligent, this was an animal that could almost always translate the most fearsome psychological questions to “am I big enough,” and for whom the answer was almost always “yes.”

The only message I could hope to send, if it was indeed enough, was that this fight was ultimately unnecessary. However, at some level, rather like a slow-witted bully, I think he continued to believe that the simplest resolution would be to stomp and tusk me to fragments.

But the elephant held his position, and I mine, threat to threat, until the rest of the herd had watered. Then, turning his back to me dismissively and drinking his fill, he followed them as they ghosted back into the brush-lands.

I of course paced off his nearest tracks, banking that information as would any creature determined to survive, and then returned to my reading of the waterhole bank. When terrible meets terrible, it seems, only kindness can win...but never if you run away.