Risingshadow has had the honour of interviewing Rhys Hughes.

Rhys Hughes was born in 1966 and began writing from an early age. His first short story was published in 1991 and his first book, the now legendary Worming the Harpy, followed four years later. Since then he has published more than thirty books, his work has been translated into ten languages and he is currently one of the most prolific and successful authors in Wales. Mostly known for absurdist works, his range in fact encompasses styles as diverse as gothic, experimental, science fiction, magic realism, fantasy and realism. His main ambition is to complete a grand sequence of exactly one thousand linked short stories, a project he has been working on for more than two decades. Each story is a standalone piece as well as a cog in the grand machine. He is finally three-quarters of the way through this opus.

Click here to visit the author's official website.

Click here to visit the author's blog.

Click here to visit the author's Facebook page.

Click here to visit the author's Twitter page.

AN INTERVIEW WITH RHYS HUGHES

1. Could you tell us something about yourself in your own words?

I was born in Wales many years ago, in 1966 in fact. They say that “if you can remember the 60s you weren’t there” and I barely remember that decade, so by such logic I was at least partly there, and checking the facts I discover that yes, I was. This shows how true and wise such sayings can be! I have travelled a lot since then and I ended up back in Wales, but for how long I’ll remain here I can’t say. I have plans to leave at the end of this year. We’ll see. I tend not to talk much about my private life, to be honest, as the temptation is to make it sound better and more exciting than it is, but I’ve been privileged to have had certain adventures and the fact that the world is full of further adventures to be had is something that always keeps me going.

As for my writing life, I have written many books and many stories so far and I’m often told that I write too fast. A famous writer advised me to “slow down” and stop publishing more than one book a year. I think that if an author writes too many books it gives the impression he doesn’t care about the quality of the work and that he is rushing. But in my own case I believe that I have no choice but to write the way I do. I get new ideas all the time and the impulse to embody these ideas in stories is an irresistible command. If I don’t use the ideas in stories they remain in my mind and cause trouble there and stop me from sleeping. So my impulse is necessity. I write to stay sane and serene, but the more I write, the more quickly the ideas come to me.

2. You've written many different kind of stories that range from experimental fiction to speculative fiction. Is it challenging or difficult to write in different genres and styles?

These days I rarely decide to write in a particular genre before I start writing a new story. Twenty years ago my fiction was more clearly compartmentalised into various genres. I would sit down and deliberately plan to write a science fiction story, a fantasy, horror or mainstream story, and I would submit the finished story to markets specialising in those genres. It was a more commercial and perhaps professional approach, though I was never massively successful back then. But now I never worry about the genre that a particular piece will be labelled as, if it’s labelled as anything at all, and targeting particular markets has ceased to be a priority for me. I’m only interested in writing just what I want to write without thinking about how I am going to sell the piece. This means that I might have to sit on a story for years before it is published, but there are many less comfortable perches than an unusual story.

I originally wanted to be a science fiction author but that desire has long since faded. I read very little science fiction now. For a long time I described myself as an absurdist, a philosophical satirist or an ironic fantasist but now I have started using the term ‘Fantastika’ to describe what I do. I am a European writer of Fantastika. I like this best. It’s a much more flexible word and it also gives me the impression or illusion that I am connecting with the authors I like best. Most writers yearn to be included in some kind of spiritual fraternity, no matter how much they champion their own individuality, and I’m no different in this respect. The instant one decides not to be constrained by genres, there is no difficulty in writing in different styles, because you are still writing in one grand overall style, the vastly broad style of Fantastika.

3. Do you have any particular favourite genre?

I find it difficult to use genre labels to classify my favourite books, other than simply referring to them as examples of Fantastika. For example, The Cyberiad by Stanislaw Lem is an almost perfect blend of science fiction, fantasy, whimsy, humour, satire, fairy tale, philosophy and speculative literature. It seems unfair to pin down such a work to just one traditional genre. The same is true of Italo Calvino’s Our Ancestors or Boris Vian’s Froth on the Daydream. This is a type of writing fairly common in the literatures of mainland Europe but less so in the English speaking world. I enjoy and identify more strongly with certain French, Italian, Russian, Czech and Polish writers than I do with writers from my own Anglophone culture. It’s just a question of taste, of course. Calvino has been my favourite author for twenty years and I still have no idea what genre he wrote in. Some of his books are delightfully whimsical, others are absolutely rigorous, some like Cosmicomics favour the mind, others like Marcovaldo favour the heart, some like The Castle of Crossed Destinies are examples of extremely tightly structured form, others like The Path to the Nest of Spiders are loose and almost rambling narratives. I like all his work. Unfortunately publishers and the market demand labels. I do my best to resist.

On the other hand, I do tend to talk about OuLiPo rather a lot, though it’s not actually a genre, more a desire or invitation to take part in an experiment that involves applying arbitrary mathematical or logical constraints to a piece of writing in order to provide a framework that breaks a writer out of instinctive and reflexive patterns. Famous OuLiPo techniques include writing a novel without the use of a particular vowel, as Georges Perec did with A Void, leaving out the letter ‘e’, the challenge being to make the novel read smoothly and as naturally as it would do had the constraint not been applied. But the point of the constraint is to limit the obvious choices a writer can make, forcing him or her to be more inventive with solutions. Calvino was an OuLiPo writer from time to time. So was Raymond Queneau, another favourite of mine. I plan one day to write a novel wholly determined by various OuLiPo constraints, both those already established and ones I must invent. It will probably be my least popular book ever, but one driven by other considerations than sales. The title of my book will be Comfy Rascals but I have no idea when I’ll begin to write it, when it will be finished or if it will ever be published.

4. How would you describe your stories to readers who haven't yet discovered them or read any of them?

I like to think that they are amusing, original and unpredictable. My quest is to entertain the reader, enthral the reader, perhaps even change the reader. In this sense I try to keep Cocteau’s dictum in mind. “Astonish me!” but it is difficult for writers to offer a viable definition of themselves. Never trust a self-definer! The important thing for me is to always strive for my best, to give to the reader something new, something that, to the best of my knowledge, they won’t have encountered before. But this of course is a somewhat implausible mission, for the simple reason that the work of every writer must resemble, more or less successfully, aspects of the work of those other writers who have influenced or mentored them. Throughout my writing life I have encountered authors with a style or approach that I urgently wanted to make my own, and those styles and approaches were very diverse. One learns from this desire to emulate and the synthesis of many such attempted emulations are what eventually forge a style that seems, and is, unique and individualistic.

Earlier this year I discovered a writer previously unknown to me by the name of Slawomir Mrozek. I instantly connected with his work and felt in his pages that I had met a kindred spirit. His short, imaginative stories, propelled to their conclusions by an absurdist and lateral logic, the whimsical tone hiding a serious intent, the troubling joys of the imagery, made me feel that here was a writer I could comfortably use as an exemplar of what I do or aspire to achieve. We encounter authors who influence us, but equally often we meet writers when it is too late for them to inspire us in that way because we are already on the same wavelength, writers who dream parallel dreams to our own, who reinforce our faith in what we are doing, and in many ways these authors are more vital and important than those who influence us. Reading them is like peering into the depths of an old mirror and seeing a distant reflection that has been there a long time, waiting for someone to come and recognise themselves, a reflection that precedes in time the object being reflected.

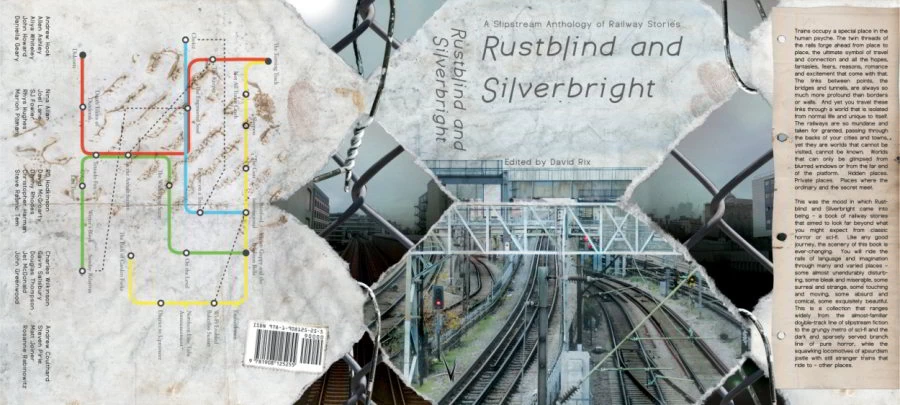

5. Your stories have been published in many magazines and in several anthologies, including the anthologies Blind Swimmer (Eibonvale Press, 2010) and Rustblind and Silverbright (Eibonvale Press, 2013). "The Talkative Star" and "The Path of Garden Forks" that were published in these anthologies are brilliant stories that differ nicely from each other. Where do you find the inspiration to write stories that differ from each other? Have any authors, books or stories been a source of inspiration to you when you've written stories?

5. Your stories have been published in many magazines and in several anthologies, including the anthologies Blind Swimmer (Eibonvale Press, 2010) and Rustblind and Silverbright (Eibonvale Press, 2013). "The Talkative Star" and "The Path of Garden Forks" that were published in these anthologies are brilliant stories that differ nicely from each other. Where do you find the inspiration to write stories that differ from each other? Have any authors, books or stories been a source of inspiration to you when you've written stories?

I am influenced by ideas, experiences, daydreams and yes, of course, by other authors. The authors that have influenced me, who are my favourite writers, tend to have wide imaginations and a restless inventiveness. I have mentioned Calvino and Lem, but Borges was an enormous influence for most of my life, precisely because of the precision of his astoundingly original concepts, the rigorous working out of paradoxical premises. Milorad Pavic freed me from the shackles of worrying about restraint when it came to language, his metaphors being the strangest, most bewildering and ecstatic in modern literature. Cabrera Infante showed me that wordplay is an invigorating and even sensual game not to be ashamed of, despite the universal sneers of critics. Yet there are writers I adore who haven’t at all filled me with the desire to emulate. I am a pure reader when I read them, intrigued and enriched by their work but without seeking to pick up clues or techniques, without wanting to learn anything just for the sake of applying it later. Kundera, Kadare, Saramago, for instance. I merely bathe in the words, wallow and refresh in the excellence.

As for the actual music of my prose, its cadences, that has been strongly influenced by three writers in particular: Donald Barthelme, Flann O’Brien and Boris Vian. I would like to think my style is a satisfying amalgam of the tones, rhythms and inflexions of each, rather than a muddy hodgepodge, but who am I to make such judgments? An author is never the best judge of his own work. I happen to think I’m a talented writer, but I might not be. That’s the danger. It’s not possible to have a view of the totality from the inside, so we must be very careful when making statements about ourselves and our work. It’s too easy to become deluded, to lose focus on reality. My books don’t sell especially well, so I am clearly not a popular writer. Is that the fault of contemporary culture or myself? A certain level of humility must be maintained at all costs. I will never stop learning, or at least I hope I never will, for that would be the end of me. I would then best serve myself by giving up altogether. And in fact one day I do plan to stop, not just to fade away imperceptibly.

As for the actual music of my prose, its cadences, that has been strongly influenced by three writers in particular: Donald Barthelme, Flann O’Brien and Boris Vian. I would like to think my style is a satisfying amalgam of the tones, rhythms and inflexions of each, rather than a muddy hodgepodge, but who am I to make such judgments? An author is never the best judge of his own work. I happen to think I’m a talented writer, but I might not be. That’s the danger. It’s not possible to have a view of the totality from the inside, so we must be very careful when making statements about ourselves and our work. It’s too easy to become deluded, to lose focus on reality. My books don’t sell especially well, so I am clearly not a popular writer. Is that the fault of contemporary culture or myself? A certain level of humility must be maintained at all costs. I will never stop learning, or at least I hope I never will, for that would be the end of me. I would then best serve myself by giving up altogether. And in fact one day I do plan to stop, not just to fade away imperceptibly.

6. You've regarded The Smell of Telescopes (Tartarus Press, 2000; Eibonvale Press, 2007) as your favourite book. It is said to be one of the funniest and most intelligent books from the lighter side of macabre ever published. Could you tell us something about this short story collection and its contents? What can readers expect from it?

6. You've regarded The Smell of Telescopes (Tartarus Press, 2000; Eibonvale Press, 2007) as your favourite book. It is said to be one of the funniest and most intelligent books from the lighter side of macabre ever published. Could you tell us something about this short story collection and its contents? What can readers expect from it?

I feel that I am always saying that such-and-such a book is my favourite and it has probably reached an absurd stage now where all my books have been rated as my absolute personal favourite at some point. But yes, I do happen to believe that The Smell of Telescopes has something special about it. There are several reasons for this. Chiefly the stories included in the collection were written when I still had a powerful sense of optimism about the writing world and my own place in it. I wasn’t yet disillusioned at all. I have always been an optimist; it’s an essential part of my character, but the point of being an optimist is that one is reacting positively to the disappointments of the world. So the disappointments have to be there in order for the optimist to exist and thrive as an optimist, for the optimist to apply their optimism to whatever they happen to be doing at the time, to their dreams, struggles and strivings. I won’t say that since I wrote that book any pessimism has crept into my outlook, staining the optimism, but I feel that a certain amount of realism has. There’s a difference between pessimism and realism. I am more realistic now about the peculiar vagaries of the writing world, its traps and injustices, politics and manipulations. Clearly my work was fresher back then as a consequence, and purer.

I’m now going to claim that my novel The Percolated Stars, which dates from roughly the same time period, is actually my best book. It was published by a disagreeable and incompetent publisher who neglected to pay me and who still forgets to pass on any royalties it earns. And it does still sell. Therefore I am reluctant to recommend it as a book for my readers to buy and I’ll remain reluctant until it is reissued by a better publisher, which is something that might happen next year. There are enough very fine publishers left in the business to stave off bitterness. Like any other commercial activity, writing and publishing books has its share of frauds, fakes and fibbers. Let’s not dwell on them but be relieved that good people are still out there, dealing fairly with their writers and helping to fill with the world with new books. Not that the world actually needs new books, but we always believe we need to be part of the process. The world doesn’t need any more babies either but that doesn’t stop us from making them. All writers should be first and foremost readers, in other words spectators of the dramas and comedies devised on our behalf, but we feel an urgency to jump out of the audience, climb on the stage and perform.

I’m now going to claim that my novel The Percolated Stars, which dates from roughly the same time period, is actually my best book. It was published by a disagreeable and incompetent publisher who neglected to pay me and who still forgets to pass on any royalties it earns. And it does still sell. Therefore I am reluctant to recommend it as a book for my readers to buy and I’ll remain reluctant until it is reissued by a better publisher, which is something that might happen next year. There are enough very fine publishers left in the business to stave off bitterness. Like any other commercial activity, writing and publishing books has its share of frauds, fakes and fibbers. Let’s not dwell on them but be relieved that good people are still out there, dealing fairly with their writers and helping to fill with the world with new books. Not that the world actually needs new books, but we always believe we need to be part of the process. The world doesn’t need any more babies either but that doesn’t stop us from making them. All writers should be first and foremost readers, in other words spectators of the dramas and comedies devised on our behalf, but we feel an urgency to jump out of the audience, climb on the stage and perform.

7. Your book, Tallest Stories (Eibonvale Press, 2013), contains 60 linked stories and 60 illustrations, and was 18 years in the making. What inspired you to write this fantastic book about a pub that lies in another dimension and where the only currency that matters is stories? Are any of the fascinating characters in this book based on real people?

7. Your book, Tallest Stories (Eibonvale Press, 2013), contains 60 linked stories and 60 illustrations, and was 18 years in the making. What inspired you to write this fantastic book about a pub that lies in another dimension and where the only currency that matters is stories? Are any of the fascinating characters in this book based on real people?

This book grew organically. I had no idea I was writing a book of linked short stories until I had already written a dozen of them. Then it occurred to me that they would fit well into a sequence if a suitable frame was provided and if the sequence was extended. That original story-cycle consisted of 20 stories and has the title of ‘Taller Stories’ and it forms the middle section of my book Nowhere Near Milk Wood. Years later I wondered if this story-cycle needed some kind of sequel, so I created a second set of linked tales called ‘More Taller Stories’ and joined it together with the first story-cycle. I felt I had created a new book, but one that was deficient in some way. I allowed the problem to work itself out in my subconscious for a few more years before creating a third story-cycle, ‘Last Taller Stories’, which I joined to the preceding pair. Now at last I was satisfied. Each of the story-cycles is held together by a framing device and these framing devices are framed by a larger framing device. Some of the separate stories also work as framing devices, not only to frame other stories but also to frame other framing devices. It’s rather complex and intricate but it wasn’t designed to be so at the beginning. It just happened to end up that way.

The sixty stories in the book can all be read as standalone pieces but it’s interesting to me how they acquire almost a different character when read next to other stories in the sequence. It’s almost as if they are changed on some deep level by events that occur in stories that at first may seem unconnected to them. So I regard this collection as a shifting mosaic of tale telling, and I don’t think I would have been capable of making it act in this fashion if I’d deliberately tried to do so at the outset. As for the characters being based on real people, the pub that lies at the core of the book is frequented by famous writers as well as hosts of invented characters, but those are the only ones who are supposed to be who they really were, apart from in the scene where a convention of fantasy writers is taking place and the list of attendees does include people I personally know. I am fond of ‘Tuckerization’, which is the habit of turning friends and colleagues into fictional characters, but there’s not much of that going on in Tallest Stories, which on the whole is a happy and trouble-free book.

The sixty stories in the book can all be read as standalone pieces but it’s interesting to me how they acquire almost a different character when read next to other stories in the sequence. It’s almost as if they are changed on some deep level by events that occur in stories that at first may seem unconnected to them. So I regard this collection as a shifting mosaic of tale telling, and I don’t think I would have been capable of making it act in this fashion if I’d deliberately tried to do so at the outset. As for the characters being based on real people, the pub that lies at the core of the book is frequented by famous writers as well as hosts of invented characters, but those are the only ones who are supposed to be who they really were, apart from in the scene where a convention of fantasy writers is taking place and the list of attendees does include people I personally know. I am fond of ‘Tuckerization’, which is the habit of turning friends and colleagues into fictional characters, but there’s not much of that going on in Tallest Stories, which on the whole is a happy and trouble-free book.

8. Many of your stories have delightfully absurd, clever and quirky humour in them. Have you always enjoyed writing humorous stories?

Humour is important to me and I have attempted to write funny or witty stories since I started writing, but humour has its particular hazards and one of the most lethal is the fact that humorous effects are not graded as smoothly as those of tragedy, suspense or wonder. We might be less moved by a sentimental tale of love than the author hopes, but still we will be a little moved. We might be less scared and shocked by a horror narrative than a back cover blurb would have us be, but still we might be a little shocked. However, to be only mildly amused by an uproarious comedy is a mark of the author’s total failure. This doesn’t mean that comedies which aren’t really funny should always be avoided, for they may have other qualities that more than compensate for the lack of main effect. The comedies of Aristophanes don’t elicit uncontrolled guffaws from me, but I still find them worthwhile and inspiring. Humour does date badly, certainly less well than tragedy, yet I regard comedy as the more perfect artform, precisely for the reason that the experience it provides, when it works properly, can never be repeated with the same intensity. It discharges its energy into the reader at the first exposure, exhausting itself by doing so and thus changing itself. The first time I read The Ascent of Rum Doodle, I laughed so forcefully I literally fell off my armchair. The second time, I remained seated and only tottered a little on the upholstered edge. The third time, I remained deeply ensconced, comfortable on the cushions, only my eyebrows moving.

And yet W.E Bowman’s parody of mountaineering literature remains my favourite comic novel, with the possible exception of his other masterpiece, The Cruise of the Talking Fish. I am grateful to him for sending me into paroxysms of mirth. I opened those volumes, began to read and the lightning bolt of hilarity leapt out and pierced my mind. Something was transferred from the page to my soul, leaving the page exhausted. That page was now weak or dead. A precious gift had not been shared with me, as with tragedy, but given entire. This seems a very generous phenomenon and is the reason I regard the best humorous writing with such awe and reverence. But I don’t wish to make it seem I believe there’s only one form of comedy with a single function. Some humorous writing might act as a carrier wave for sadness, as with John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, or rage, as with B.S. Johnson’s Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry, two of my favourite novels. But yes, to answer your question, I do enjoy writing humorous stories, I enjoy the attempt thoroughly.

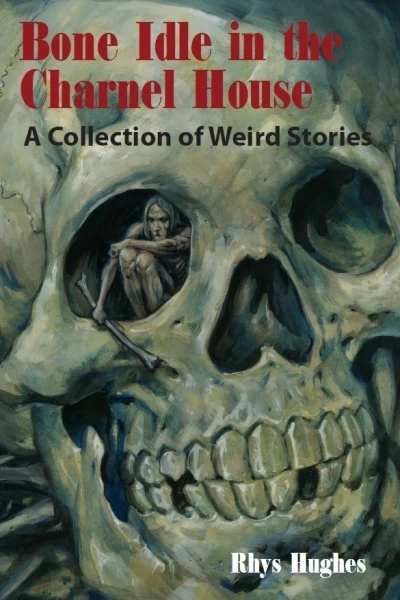

9. You've also written stories that represent the weirder side of speculative fiction and can be categorised as Weird Fiction. These intriguing stories were recently published in Bone Idle in the Charnel House (Hippocampus Press, 2014). Could you tell us a bit about these stories and what inspired you to write them? Are you planning on writing more of this kind of fiction in the near future?

9. You've also written stories that represent the weirder side of speculative fiction and can be categorised as Weird Fiction. These intriguing stories were recently published in Bone Idle in the Charnel House (Hippocampus Press, 2014). Could you tell us a bit about these stories and what inspired you to write them? Are you planning on writing more of this kind of fiction in the near future?

As I said before, I don’t really make any distinction between genres now, so the stories of mine that are regarded as serious ‘weird’ fiction are regarded that way simply because an editor or publisher chooses to do so. In the case of Bone Idle in the Charnel House, I was approached by S.T. Joshi to put a new collection together. I sent him batches of stories and he accepted some and rejected others. At the same time I was putting together a collection for Tartarus Press, Orpheus on the Underground, and frequently stories rejected by one of the editors would be accepted by the other. I seemed to lack all foresight as to which of my stories would appeal to that particular editor or not. I just sent them stories of mine that hadn’t yet appeared in any of my books and allowed them to make the selection. Finally both books were deemed ready.

This method is quite unlike the way I created The Smell of Telescopes or Tallest Stories, but as I get older I become less controlling, less perfectionist. That Tartarus collection, for example, was the first book of mine with a title not chosen by myself. I simply hadn’t settled on a title for it, though I was thinking of calling it Corybantic Fulgors. In the end the publisher took the title of a story included in the collection and used that as the overall title. In the past I probably would have objected to this, because I had a rule that a collection of stories must have a title unique to itself, but now I care less about such rules. This is what I mean when I say that realism has watered down my optimism, though to those I deal with in the writing business, that kind of ‘optimism’ probably appears more as stubbornness and an overbearing desire to be in charge. I don’t protest much at editorial changes these days, unless the changes really are drastic and wrong. If I ever become successful enough for all my work to be reissued, I’ll insist on it being published the way it was originally written. It just means being patient, and hopeful, and lucky. And Corybantic Fulgors will undoubtedly be the title of a future collection. Waste not, want not.

This method is quite unlike the way I created The Smell of Telescopes or Tallest Stories, but as I get older I become less controlling, less perfectionist. That Tartarus collection, for example, was the first book of mine with a title not chosen by myself. I simply hadn’t settled on a title for it, though I was thinking of calling it Corybantic Fulgors. In the end the publisher took the title of a story included in the collection and used that as the overall title. In the past I probably would have objected to this, because I had a rule that a collection of stories must have a title unique to itself, but now I care less about such rules. This is what I mean when I say that realism has watered down my optimism, though to those I deal with in the writing business, that kind of ‘optimism’ probably appears more as stubbornness and an overbearing desire to be in charge. I don’t protest much at editorial changes these days, unless the changes really are drastic and wrong. If I ever become successful enough for all my work to be reissued, I’ll insist on it being published the way it was originally written. It just means being patient, and hopeful, and lucky. And Corybantic Fulgors will undoubtedly be the title of a future collection. Waste not, want not.

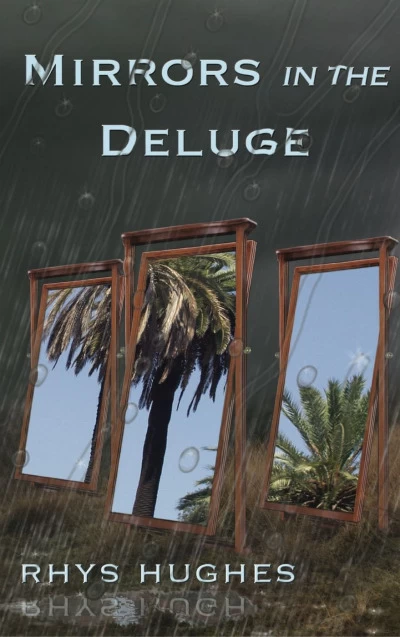

10. Your latest book, Mirrors in the Deluge (Elsewhen Press, 2015), was published a while ago. It's an intriguing collection of 32 stories. How would you advertise this short story collection to your readers?

10. Your latest book, Mirrors in the Deluge (Elsewhen Press, 2015), was published a while ago. It's an intriguing collection of 32 stories. How would you advertise this short story collection to your readers?

In some ways this collection is the best introduction to my work as a whole. This isn’t entirely true, as it lacks my serious stories, the longer work, the intricate multi-plotted narratives, but it perfectly demonstrates my tone and style. So a new reader who doesn’t enjoy this book probably won’t enjoy my other work. The stories in this collection all have a lightness of touch and they are driven by a logic that isn’t always the logic of everyday cause and effect but often that of word-association or the lateral connectivity of concepts. I find myself writing these kinds of stories very easily. When I imagine a story of this kind that I want to write I often see it as a film in my imagination, but not a complete film. Only a few scenes are revealed to me. It’s more like finding an album of photographs and trying to find a story that will make a connection between the different pictures. Almost always I have these ideas and pictures in my mind wherever I go. That is my inner life. Where these images come from originally I don’t know. I just accept them.

11. You have an ambition to complete a grand sequence of exactly one thousand linked short stories. Could you tell us something about this project?

I want my own ‘1001 Nights’ and I realised that I wanted this after I had written maybe 200 stories. I doubted I would ever get to my target but it seemed nice to have a goal anyway. In the past five or six years my rate of production increased to the point where the goal actually started to seem attainable. I’ve just finished writing my 772nd story and by the time this interview is published I’ll probably have added at least one or two more stories to this total. The purpose of linking all my stories in one gigantic story-cycle is threefold. Firstly I am Welsh and as a nation we tend to be averse to grandiose schemes. This aversion is intolerable to me. I need to oppose this timidity of ours. Hence my grand wheel of stories, the entirety of which I intend to call PANDORA’S BLUFF, when or if it comes to fruition. Secondly, I don’t want to be one of those writers who fade out like an echo, who just keep going until they attenuate themselves. I want there to be a definite full stop to my career, the thousandth and ultimate tale! Thirdly, the scheme satisfies my cravings for numbers, for numerology. It gives the illusion that there is order in the chaos of my strivings.

12. What are you currently working on?

I always work on many different projects simultaneously. If I provide a list of works in progress I will be sure to leave some out and I’ll regret that later. But I will briefly mention that I have started writing a book that is neither a novel nor a collection of short stories but something in between, a set of interviews with the triple-headed dog that guards the entrance to Hades. This dog has met many mythical figures who have passed him in spirit form after their deaths, and he is in the position of being able to recount lively impressions of them to a reckless journalist. The title of this book is Down Cerberus! and I have no idea when it will be completed, much less whether it will be published.

13. Is there anything you'd like to add?

I would like to say a big hello to all my wonderful friends.